Cling on for dear life is a blog dedicated to CB 750 Café Racers and other cool motorcycle stuff.

Monday, 30 April 2012

Honda Hawk Streamliner Week – Post: 08

I would personally like to thank Dick Keller for making

The Honda Hawk Streamliner Week possible.

Without Dick Kellers info and pictures this fantastic journeay down memory lane would not have been possible.

I hope you all injoyed the stories and the documentation of the Honda Hawk projetct, and hope that we will see you soon here on COFDL.

With warm regards, The Pilot

Honda Hawk Streamliner Week – Post: 07

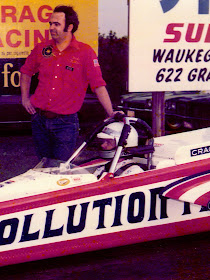

DICK KELLER - SPACE AGE SPEEDSTER

Father of the Honda Hawk

Few

men have realized the acclaim and successes in land-speed-record

(LSR) racing and motorsports design innovation as Richard “Dick”

Keller; project manager of Reaction Dynamics’ successful The

Blue Flame rocket-powered LSR racer which streaked to the

world record speed of 630 miles per hour; designer and builder of the

Honda Hawk motorcycle streamliner; rocket engineer,

chassis consultant and designer for the Pollution Packer and

Pollution Packer Bonneville Dragster race cars which

set numerous national, international, and world records on the

Bonneville Salt Flats; and designer of the first successful

rocket-powered race car, the X-1.

How

did this fascination with speed and rockets begin? As a boy, Dick saw

a photograph of auto magnate Fritz von Opel’s rocket car that had

achieved a speed of 121 miles per hour at Berlin’s Avus track in

1928. Emblazoned on the car in large letters were the initials RAK2,

a German abbreviation for the word “raketen”, or rocket, number

two. Young Dick, whose initials are RAK III, imagined the coincidence

to be Destiny pointing a finger at him. Thereafter, rocket propulsion

and motor racing became his greatest interests and enjoyment.

Dick

seemed always in a hurry to get somewhere fast. He earned a

reputation amongst his playmates in his Chicago neighborhood for

modifying bicycles to go faster, stripping off excess weight and

changing the sprockets for more speed. Using war surplus CO2

cartridges for jet propulsion, he built (and wrecked) numerous balsa

wood model Bonneville lakesters.

While

a teenager he built and drove “hot rods” on Chicago streets and

dragstrips as a founding member of the Igniters Auto Club. Then, in

the late Fifties, he was further inspired when he became an

occasional “go-fer” for the greatest dragracing star of all time,

Don “Big Daddy” Garlits.

Continuing

his education after high school at Notre Dame University and Illinois

Institute of Technology, his professional career has spanned

fundamental and applied research as well as engineering design,

development, and management. Early career highlights include research

on aircraft boron fuels and silicone lubricants for the US Air Force,

design of high vacuum test equipment used in developing new

semi-conductor materials and integrated circuits, chemical warfare

projectiles, military satellite defenses, NASA rocket-fueling

monitors for the Saturn I and Saturn V Apollo booster rockets, and a

study of the gas reaction kinetics of methane and oxygen.

Experience

gained at Phoenix Chemical Laboratory, IIT Research Institute, and

the Institute of Gas Technology, in industrial and government

contract research, led to his co-founding Reaction Dynamics, Inc.

with Ray Dausman and Pete Farnsworth in 1965 to design, build, and

develop new concepts in prototype and racing vehicles. There, he and

Ray, who also worked with him at IIT Research Institute, designed and

developed the first hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)

rocket motor for a racing car, the X-1. Its record-setting

speeds on Midwestern dragstrips eventually helped Dick convince the

American Gas Association to sponsor what was to become a successful

attempt on international speed records. On October 23, 1970, Gary

Gabelich, Long Beach, California native, drove The Blue Flame

rocket to a new FIA-recognized kilometer world land-speed-record

of 630.388 miles per hour.

In

1971 at Reaction Dynamics, Dick and Pete designed and built the Honda

Hawk, a turbocharged dual 750cc 4-cylinder motorcycle-engine

powered land missile that zoomed across the Bonneville Salt Flats at

286 miles per hour, more than 30 mph faster than the FIM world record

at that time. Unfortunately, due to poor surface conditions that

year, the required backup run for the official record could not be

made.

After

leaving Reaction Dynamics in 1972, Dick continued racing car design

and building rocket propulsion systems as Keller Design Corporation.

His engines have powered the Pollution Packers, Miss

STP, Conklin Comet, and American Dream

Rocket Dragsters, and the Spirit of ‘76,

Captain America, Moonshot, Chicago

Patrol, Vanishing Point, and Natural High

rocket-powered Funny Cars.

The

Pollution Packer Bonneville Dragster, a unique

monocoque-chassis Rocket Dragster, was designed by Keller and built

by Tim Kolloch at R&B Automotive in Kenosha, WI. In addition to

the World Land Speed Record, Dick’s cars held, at the same time,

all FIA world acceleration and speed records up to one

kilometer distance (see FIA Recognized International Record list).

Numerous dragstrip records set coast-to-coast included the all-time

NHRA low elapsed time (4.62 seconds) and top speed (344 mph) for the

1/4-mile in an NHRA national event by Dave Anderson driving the

Pollution Packer at the NHRA Summernationals in 1973, and the

1/8-mile (3.40 seconds ET at 248 mph) in 1974. Sammy Miller

ultimately blasted his Keller Design-powered Rocket Funny Car, the

Vanishing Point, to over 400 miles per hour in 4.04 seconds

in 1977!

Dick’s

competitive urges turned full circle when, as a Masters Category

competitor, he returned to his early love, bicycle racing. He was won

several national track championships as well as setting European

(UEC) and World (UCI) masters track cycling records.

Beginning

with a young boy’s fascination with (sp)rocket technology,

continuing through a young man’s determination to excel, Dick

Keller’s quest for speed has certainly been

rewarded

with success.

To

quote Dick in his 70s, “Life is short; the road is long; ride

fast!”

Friday, 27 April 2012

Thursday, 26 April 2012

Honda Hawk Streamliner Week – Post: 05

The Motorcycle World Speed Record?

It

is the big day, and the Honda Hawk needs to show the world that it is

ready to fly into the history books, and take the motorcycle world

speed record. The FIM observer has just been flown in from Europe,

and he stands next to maybe the greatest American pre-World War II

motorcycle racer, Joe Petrali, here on the salt flats of Bonneville.

Joe Petrali is here as timekeeper for the USAC, and together with FIM

they are the ones who will perpetuate this great event in the years

to come (if succesful).

Left: FIM

observer Right: Joe

Petrali

Everything

on the Honda Hawk is being checked and re-checked before pilot Jon

McKibben will take the first test run down the salt. The side panels

is sitting next to the Hawk, as the Honda mechanics makes the final

adjustments to the speed machine. Anytime from now could be "Go"

for the first run of the day...

Jon

McKibben's instrument panel looks like it was taken out of an

airplan. The

far left gages read the cylinder head temperatures of the two CB750s,

and the two gages on the center right read pressures to the two

stabilizing struts that are deployed to keep the Honda Hawk upright

as it slows down and stops. Top right is the clutch servo-assist

cylinder pressure, the lower right is the turbocharger manifold

pressure with the fire extinguisher knob visible below. Not seen [on

the picture below] is a panel between the rider’s legs with two

columns of lights, one for each gear plus neutral. Because both

transmissions were shifted with a common linkage, McKibben would

check after each shift that both gears were engaged before releasing

the clutch lever. On one run they did get out of synch and the run

had to be aborted.

Jon

McKibben gets into the cockpit of the Hawk, and the crew push the

Hawk to a running start... But already on this first run it is clear

that something is wrong!The

steering geometry is not stable, and the steering trail is wrong. It

is clear that the front ends four-bar linkage steering design, is not

working as intented. Reaction Dynamics wants to adjusted the trail, but,

the pressure from above is very much “don’t just stand there –

do something”. After

several failing attempts to run the bike, due to instability, it is

decided to revert to a proven “center-point steering” design such

as Don Vesco had developed for his successful record run in 1970 with

his Yamaha.

Dick

Keller then calls Don Vesco, and asked for the bearing part number

he had used – which he gladly provids. Dix Erickson then drives back to

the American Honda shop in Gardena to machine the hub and pick up the

bearings. And with minimal machining of the existing parts, there is now a

possibility that the Honda Hawk will run straight.

But the Hawk is followed by bad luck... The Bonneville salt flat was not smooth in 1971, and at high speeds the rear wheel would lose traction and sometimes became slightly airborne after hitting a rut or wavy portion of the surface. When this happened under power the engines would rev up quickly, before McKibben could roll off the throttle, and the tire would speed up. On several occasions the high revs resulted in engine damage. On other occasions the over-speeding tire would impact the surface again with a sudden change in speed due to the tire immediately slowing down to match the ground speed and over-stress the drive chain. Drive train failures were of two types, a breaking drive chain, or a chain link separating and penetrating the gearbox casting.

The

Honda Hawk made several runs in the high 200s, and made one 286.556

mph run in 1971. But with the FIM two hour rule, stating that you

need to make two consecutive runs to make a record, the Honda Hawk

team never manage to make a return run in the two hour window given by FIM.

Aftermath

Pete

Farnsworth and Dick Keller's small company Reaction Dynamics, that

had been so succesful with the record holding Blue Flame, closed

after the failure of the Honda Hawk record attempt. The financial

situation in Reaction Dynamics had depended on a bonus Honda would

have paid them, had they set the record.

American

Honda took over ownership of the Honda Hawk in 1971, and returned to

Bonneville in 1972, with a re-work rear suspension on the Hawk. In

1972 the Honda Hawk crashed at high speed, ending its career. Rider

Jon McKibben walked away from the accident, and the program was

terminated.

Wednesday, 25 April 2012

Honda Hawk Streamliner Week – Post: 04

Arrival

at Bonneville

It

is early morning on thursday the 10th november 1971, and Pete

Farnsworth and Dick Keller is driving their van out to the salt

flats, towing the Honda Hawk in its new trailer, nicknamed "The

Hawk's Nest". They pull into the small town of Wendover, west of

Bonneville salt flats, an interesting small western town stradding

the Utah and Nevada state line. Due to the predominantly Mormon

population in Utah, this is absolutely No Alcohollic Beverages

territory! Wendover is also the last urban setting before the small

group will enter the uninhibited wide-open planes of Nevada - the holy

ground for land speed records. Although tired, both men are anxious

to get out on the salt the next day. Their around-the-clock work

schedule will not end until they (hopefully) set the motorcycle world

speed record.

With

the 1970 world speed record succes, The Blue Flame, in fresh memory

Farnsworth & Keller are both very discouraged when they see the state of the salt surface! While the salt was perfectly flat and dry in 1970, 1971 is quite another story.

Recent construction work on the nearby Interstate 80 highway has left

loose debris, mud, and clay, which has washed out onto the course

during the winter rains. The course is filled with pockmarks and

undulations which promis a bumpy ride for the Honda Hawk.

On

the salt flats this day is a very concerned timing crew (Joe Petrali,

and his son David), the AMA steward Earl Flanders, and FIM officials.

Honda had a film crew ready, and Motorcyclist magazin writer Bob

Greene is taking notes in the background.

Taking the pressure

into consideration, Farnsworth & Keller are thankful for the

confidence expressed by the entourage. The Honda PR people still

think they just need to fire up the CB750s, set the record, and go

home.

Everyone

fiddeling with speed machines, knows that a new bike is really a

development project. While a lot of effort goes into the engineering,

design, and fabrication, the first running of a racer is a test

program. On this day all the people from Reaction Dynamics is aware

of this, and would like to spend the first runs with just working

crew present, to work out the kinks in the motorcycle. There will be

issues, but no one knows what the issues will be yet.

The

Honda crew was led by Bob Young and Dix Erickson. Dix had worked for

Reaction Dynamics on The Blue Flame the previous year, before taking

a job at Honda in California. Dix was actually the guy responsible for

bringing American Honda and Reaction Dynamics together on this

venture, by showing some preliminary designs of the Hawk to

his boss at Honda.

The

American Honda crew had brought with them a supply of engines, and

several engine adapter kits (sprockets, chains, mounting frames,

etc.), which they assembled in the Western Mobil gas station garage.

The 3 to 4 Honda mechanics worked their tails off rebuilding the

motors and helping wherever they could, under the amazing guidance

from Bob Young. The two very different organizations start working as

a functioning team, and as a result they were able to overcome the

challenges they faced in 1971. The team kept pushing towards the world

record, but the weather brought the record attempt to a halt just as

the record was in their grasp...